The epochal Ninth was heard for the first time 200 years ago. But how does Beethoven’s composition actually work? What special moments can we as listeners discover in the symphony? Bennet Eicke, conductor and musicologist, takes you on a listening journey. In preparation for the concert at Beethovenfest 2024 – or, if you haven’t secured a ticket, simply to immerse yourself in the anniversary work.

Listening Guide for the Beethoven anniversary

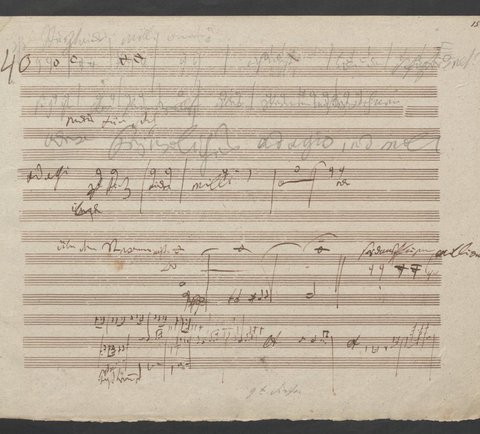

Symphony No. 9

Relentless joy

Pulse and dramaturgy in Beethoven’s Ninth SymphonyIt is always difficult to put yourself in the position of having heard something for the first time – especially when it comes to a work of monumental power such as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. As the European anthem, »Freude, schöner Götterfunken« has a firm place in our everyday lives. This makes it all the more important to return to the seats of the Kärtnertortheater in Vienna in May 1824 and to understand the meaning of the last movement with this anthem in the context of the entire work.

I. Movement

This begins in the very first bar: There is the sound of a horn fifth (two horns with an open-seeming harmony), underneath a quivering rhythm in the strings – like a primal sound. The first movement is characterised by a pulse, small rhythmic motifs (a concise ›short-long‹), which form a larger whole and break out into the dramatic.

In this way, the larger process emerges from the smaller – the musical themes are cells from which Beethoven builds transitions and leads from one point to the next. This also applies to the second melodic shape of the movement, called the secondary theme. It only becomes recognisable as a ›melody‹ through its division between different instruments.

Or in the development, as the middle, turbulent section of the first movement is called, in which Beethoven leads a part of the opening motif into the return of the first theme in a breathtaking fugue with a biting pulse – does it sound like the major key here? Exciting things happen here in every voice involved: the cellos and basses pound the significant major third into the sound at this great climax. In other words, the note that was completely missing from the chord at the beginning of the movement, leaving it hovering undecided between major and minor. However, the major key does not last long, the conclusion of peace is still a long time coming.

II. Movement

In the second movement, called Scherzo, the pulse breaks in like an unstoppable force, only to develop from a small cell into a mighty orchestral tutti. This is where Beethoven reveals his playful side – he plays with the ratios of the bar structures (from four-note to three-note and back again) and takes the safe ground from under the listener’s feet.

The pulse remains even when Beethoven leads into the second theme – or, rather, when he rushes into it.

The final surprise awaits at the end, where he leads us to expect a longer section, only to break off and find a ›shorter‹ way out.

III. Movement

The momentum pulse can also be found in the warmest notes of the third, slow movement. Two simple melodies alternate and are gradually led through variations – the pulse remains the same, however, with faster note values. The forest thus becomes denser, although never hectic – which suits the fourth horn well when it has its brilliant solo moments in this movement. It plays gently accompanied by clarinets and flutes.

IV. Movement

And the fourth movement bursts into this idyll like a primal force – violent and decisive. Cellos and basses melodise, a singer’s recitative without a singer! The orchestra responds with flashbacks to all the previous movements, including a small foretaste of what is to come. And then, out of nowhere, this familiar theme emerges, growing into the whole orchestra to give way to the triumphant drama.

The solo baritone finally celebrates his entrance: »Oh Freunde, nicht diese Töne« (»Oh friends, not these notes«), and the choir sings »Freude, schöner Götterfunke« (Joy, beautiful spark of God«).

A small oratorio unfolds within the symphony with a process right up to the end, everything between heaven and earth: it becomes spherical (»Such’ ihn überm Sternenzelt«, »Seek Him over the stars«), it becomes euphoric (double fugue, i.e. a fugue with two different themes at the same time), the whole world is embraced at the end.

My favourite moment here – how Beethoven brings everything to a halt with »vor Gott« (»before God«) and strikes an ›alla Marcia‹, a military march, into this expectant silence with contrabassoon and percussion – is a magnificent change of mood. When this coarse song of joy develops into a bitingly pulsating fugue and discharges in the repeated climax with chorus, we probably have to play ›other notes‹ after a general pause.

Beethoven relentlessly fights for joy with every note, making the words and chorus all the more solemn. No wonder composers found it difficult to write another symphony after this.

Beethoven’s Ninth in the festival 2024

- , Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche Berlin

Special concert Berlin: Beethoven 9

Bundesjugendorchester, World Youth Choir, Jörn Hinnerk Andresen

Dun, Beethoven

- , Bonn city centre

Opening Party: Clear the Stage for Beethoven

Students and amateurs from Bonn and the region, Bundesjugendorchester, World Youth Choir