The Catalan composer Ferran Cruixent is preoccupied with profound themes such as the mechanisation of our environment and existence, for which he finds surprising correspondences in his music, or the spiritual permeation of life. Ferran Cruixent has composed a major new work for piano trio and orchestra for the Sitkovetsky Trio, the resident ensemble at Beethovenfest 2024. A conversation about the fascination of everyday sound, mobile phones on the concert platform and the ›cosmotheandric‹ view of the world.

Composer Ferran Cruixent

Spiritual search

Let's start with the city of your birth, Barcelona – one of the most visited cities in Spain, a traditional working-class city, once the capital of anarchism, today the capital of Catalan separatism. What influence does the city have on you as an artist and as a person?

The city is of course a source of inspiration for me. I am born there, the language and the climate define me. They say that the Catalans are the Swabians of Spain: We are very hard-working and very punctual – certainly one reason why I felt very much at home when I was studying in Germany [laughs].

Does the chequered history of your country play a role in your music?

Not really, that would be too narrow a perspective for me. I prefer to observe people in general, without limiting myself to one nation. I’m interested in the values that unite us as humans. And I find that focussing on the national ultimately distracts from the most important things in life: love, the mind, the spiritual.

But every city has its own sound, of course. I have an absolute sense of hearing, and even as a child I perceived the surroundings of Barcelona musically: the yelping glissando of the underground as it enters the station, the Doppler effect of a police siren. I then made melodies from this in my improvisations. Or I remember slipping backwards on the piano stool at a concert, which made such a squeaking noise. I then spontaneously filled it in with chords – and only then did I play Beethoven’s Sonata op. 111. Later, I presented a project in Basel and at the Fundació Miró about the sound of the city of Barcelona, entitled »Urban Surround«.

Of course, as a child I didn’t really realise what I was doing. But my parents obviously saw a special potential and enabled me to study music at the conservatory. They never demanded that I take up a profession just to earn a living. On the contrary, they allowed me to live my dream. I was able to dedicate my life to music without any pressure – that was an exception in our society!

Nevertheless, there is no dream without hard work – this was apparently also the view at the conservatory in Barcelona...

Indeed, the studies were very rigorous. My piano professor Carmen Vilà has an international reputation and is friends with famous people such as Zubin Mehta, Daniel Barenboim and Alfred Brendel. She specialises in Viennese classical music, but also in Rachmaninov; and her lessons were not mechanical, they were really about making music. At the same time, however, I also had to study music theory, harmony, counterpoint, fugue, violin and singing – a tough workload!

How important is classical and contemporary music in Catalan society?

New music is currently experiencing a huge boom in Catalonia and Spain. Many composers are being offered the opportunity to work with the city’s most important concert halls. As far as classical music is concerned, there is a huge music programme with international artists. But of course you can’t compare that with the Catalan passion for football or other sports... well, it’s the same everywhere, I guess.

Your first intensive contact with contemporary music was during your studies with Dieter Acker at the Munich Academy of Music. What does ›new music‹ mean to you today?

Incidentally, I also studied film music in Munich – but that was stylistically too straightforward for me, and you have much less freedom than with concert music. For me, composed music today has the task on a philosophical level of showing the aspects of society that are obscured by the hectic pace of life to which we are exposed. For me, this means a kind of search for the deepest and most spiritual dimensions in humans – but also a clear commitment to the moment in which we are currently living. Art must be committed and somehow visionary. But also attractive! For me, music is a way of understanding society and, let’s say: Open channels for psychological and human understanding.

You like to emphasise the spiritual side of music. On the other hand, you have a pronounced interest in modern technologies – take »cybersinging«. Do you want to turn musicians into avatars?

Not quite – but I am simply very interested in the relationship between humans and technology. We have improved medicine through technology – my father was healed after a stroke – and ultimately the smartphone is an extension of our brain. I’ve been thinking about how this can be depicted in music. In »cybersinging«, which you mentioned, the performers use their own mobile phones to play audio files that I have prepared. I see this as a new way of interaction between performer and composer beyond the score.

The »Cyborg Manifesto« by the American feminist and philosopher Donna Haraway had a great influence on me. In my symphonic work »Cyborg« in 2009, I tried for the first time to transform the classical orchestra into a cyber orchestra. »Cybersinging« infinitely expands the sound possibilities of the orchestra. This basically takes me back to the game I played as a child, when I mixed urban technological sounds with harmony in my imagination. For me, this is always a poetic world created by mixing traditional musical instruments and smartphones – old and new technology.

Smartphones also play an important role in your new piece for the Sitkovetsky Trio. The title »Trinity« is associated with the Christian religion. Are you a religious person?

No, I consider myself to be deeply spiritual and connected to life, but I don’t need religion to understand the spiritual dimension of human beings. »Trinitiy« plays with different associations. We have three soloists, and we have three movements. In addition, the work is inspired by texts by the Hindu-Catalan philosopher Raimon Panikkar. In his trinitarian vision of reality, which he called »cosmotheandric«, the cosmos, God (Theos) and man (Andros) are united; everything is interdependent and cannot be thought of without the other. For Panikkar, the reality in which we live therefore consists of a spiritual dimension, a cosmic dimension and a human dimension. Only by accepting these values can there be true democracy among people, which promotes a mutual respect that elevates us. In my Concerto for Piano Trio and Orchestra, I thus interpret the motto ›Together« of this year’s Beethovenfest in my own way.

How is this togetherness expressed in the score?

In each of the three movements, I have focussed on one of the realities mentioned by Raimon Panikkar. The first movement, entitled »Vidi Aquam« (I saw water), transports us into the mysticism and ecstasy of the divine, characterised by minimalist cells of tones and harmonies that evoke a liturgical and ethereal world. It is inspired by the Gregorian chant »Vidi aquam« in the Catholic Pentecost Mass and the Hindu mantra »Om Vam Varunaya Namah«. There are various ›water sounds‹, such as the digital sounds from a mobile phone that I programmed, but also motifs from the piano or violin that flow down like water for me.

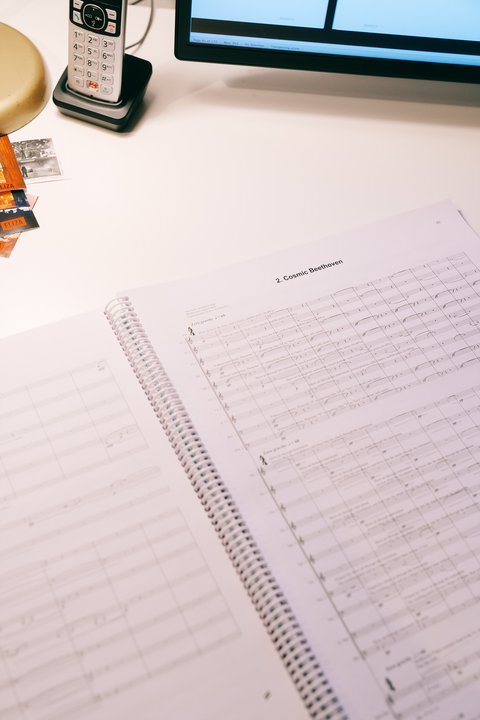

The second movement, »Cosmic Beethoven«, leads us to a cosmic vision of reality, with nostalgic echoes and resonances emanating from the cello theme in the slow movement of Beethoven’s »Triple Concerto«. The third movement, »Wild Rondo«, is indeed a virtuoso rondo, wild, earthly and frenetic – the image of a world that is increasingly leading us away from the idea of the Trinity. The entire movement is based on a narrow three-note motif that symbolises the human search for the Trinity. At the end, it culminates in a grand final celebration.

You like to emphasise the spiritual side of music. On the other hand, you have a pronounced interest in modern technologies – take »cybersinging«. Do you want to turn musicians into avatars?

Not quite – but I am simply very interested in the relationship between humans and technology. We have improved medicine through technology – my father was healed after a stroke – and ultimately the smartphone is an extension of our brain. I’ve been thinking about how this can be depicted in music. In »cybersinging«, which you mentioned, the performers use their own mobile phones to play audio files that I have prepared. I see this as a new way of interaction between performer and composer beyond the score.

The »Cyborg Manifesto« by the American feminist and philosopher Donna Haraway had a great influence on me. In my symphonic work »Cyborg« in 2009, I tried for the first time to transform the classical orchestra into a cyber orchestra. »Cybersinging« infinitely expands the sound possibilities of the orchestra. This basically takes me back to the game I played as a child, when I mixed urban technological sounds with harmony in my imagination. For me, this is always a poetic world created by mixing traditional musical instruments and smartphones – old and new technology.

Smartphones also play an important role in your new piece for the Sitkovetsky Trio. The title »Trinity« is associated with the Christian religion. Are you a religious person?

No, I consider myself to be deeply spiritual and connected to life, but I don’t need religion to understand the spiritual dimension of human beings. »Trinitiy« plays with different associations. We have three soloists, and we have three movements. In addition, the work is inspired by texts by the Hindu-Catalan philosopher Raimon Panikkar. In his trinitarian vision of reality, which he called »cosmotheandric«, the cosmos, God (Theos) and man (Andros) are united; everything is interdependent and cannot be thought of without the other. For Panikkar, the reality in which we live therefore consists of a spiritual dimension, a cosmic dimension and a human dimension. Only by accepting these values can there be true democracy among people, which promotes a mutual respect that elevates us. In my Concerto for Piano Trio and Orchestra, I thus interpret the motto ›Together« of this year’s Beethovenfest in my own way.

How is this togetherness expressed in the score?

In each of the three movements, I have focussed on one of the realities mentioned by Raimon Panikkar. The first movement, entitled »Vidi Aquam« (I saw water), transports us into the mysticism and ecstasy of the divine, characterised by minimalist cells of tones and harmonies that evoke a liturgical and ethereal world. It is inspired by the Gregorian chant »Vidi aquam« in the Catholic Pentecost Mass and the Hindu mantra »Om Vam Varunaya Namah«. There are various ›water sounds‹, such as the digital sounds from a mobile phone that I programmed, but also motifs from the piano or violin that flow down like water for me.

The second movement, »Cosmic Beethoven«, leads us to a cosmic vision of reality, with nostalgic echoes and resonances emanating from the cello theme in the slow movement of Beethoven’s »Triple Concerto«. The third movement, »Wild Rondo«, is indeed a virtuoso rondo, wild, earthly and frenetic – the image of a world that is increasingly leading us away from the idea of the Trinity. The entire movement is based on a narrow three-note motif that symbolises the human search for the Trinity. At the end, it culminates in a grand final celebration.

Ferran Cruixent’s premiere at the festival 2024

- , Opera Bonn

hr-Sinfonieorchester & Sitkovetsky Trio

hr-Sinfonieorchester, Sitkovetsky Trio, Ivan Repušić

Pejačević, Cruixent, Dvořák