Thomas Mann – an ›ultra‹? It is probably not the first association that comes to mind when thinking of the famous German writer. Ultra successful? Yes. Ultra bourgeois? Perhaps. But he certainly is not the prime example of an artistic pioneer or trailblazer of his time. However, there is one area where the word fits him perfectly: music.

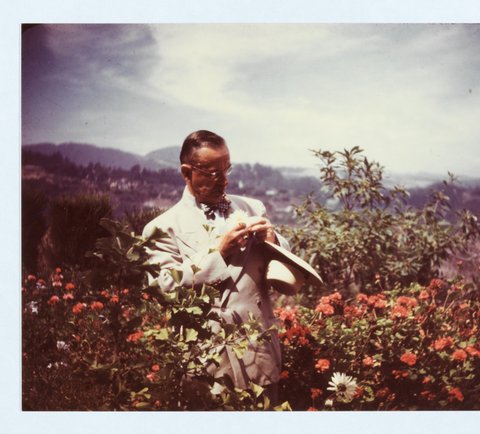

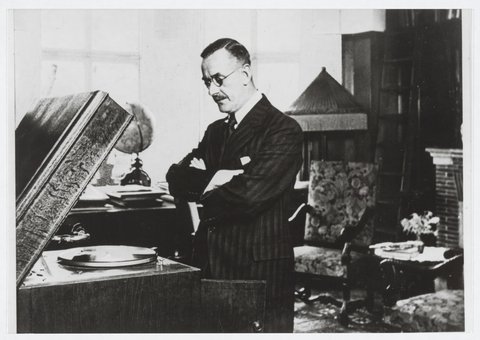

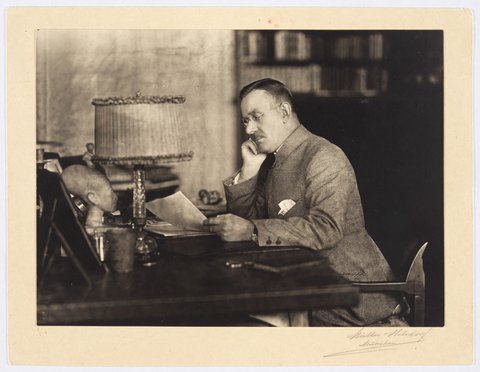

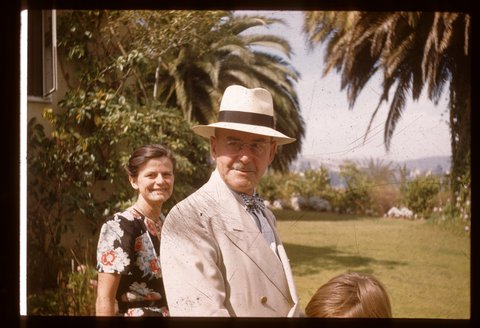

Thomas Mann

Musically Obsessed

In bookstores, podcasts, television programs: Thomas Mann’s 150th birthday is being celebrated everywhere this year. The Beethovenfest will also feature a panel discussion with current and former fellows of the Thomas Mann House. Among them is the artistic director of the Beethovenfest, Steven Walter, who will talk with his co-fellows about the politically engaged Nobel Prize winner. But what is the famous author’s relationship to music? Music is not only a core element of many of his best-known works – it is also a fateful factor in his own biography.

A fatal role model: Richard Wagner

Since childhood, Mann had been influenced by the musical impressions of his surroundings, from his mother's piano playing to his first visits to the opera, where he discovered his fascination for the music of Richard Wagner. Wagner became Mann's artistic role model. It must have been all the more unsettling for him when his speech marking the 50th anniversary of the composer's death in 1933 was met with opposition. Important cultural figures and the press launched a campaign of denunciation against him. He was accused of denigrating the »great German musical genius«.

The Nazi authorities did not ignore this public outcry. His speeches against the rise of fascism in Germany had already attracted the negative attention of the NSDAP. In the summer of 1933, while Thomas Mann was on an international lecture tour with his Wagner speech, a protective custody order was issued against him. Upon his return to Germany, the writer would now face imprisonment in a concentration camp. Mann would not cross the German border again until after the end of the war. Music sealed his fate as an exile, as an unwanted border crosser in the literal sense.

What remains when Beethoven's ninth symphony is deconstructed?

Mann explores the idea that music has a fatal power in one of his major works from his time in exile, the novel »Doktor Faustus«, published in 1947. »The life of the German composer Adrian Leverkühn, as told by a friend,« reads the subtitle. As the reference to the character Faust suggests, the novel concerns a pact with the devil that Leverkühn enters into. This promises boundless inspiration for his musical compositions. It is clear that this pact must end in disaster. With this musical novel, Mann ultimately attempts to create an allegory of Nazi Germany. As Leverkühn gradually descends into madness, his compositions stray further and further from the musical norms and boundaries of the time – his music becomes ›ultra‹ in every sense of the word.

Two composers served as role models for the protagonist: Mann’s contemporary Arnold Schoenberg (who was far from pleased with his portrayal in the novel) and Ludwig van Beethoven. In the novel, Leverkühn invents the twelve-tone music in a delusional state. With this compositional technique, he deconstructs Beethoven's late works. His magnum opus is intended to be a deliberate reversal of Beethoven’s ninth symphony. He composes the symphonic cantata »Dr. Fausti Weheklage« (Dr. Fausti's Lament), which mourns the loss of all confidence in humanity, the world, and God. The contrast to Beethoven’s final movement of the ninth symphony could not be greater. The »Ode to Joy« is replaced by a lamenting choir that sings of the meaninglessness of life in a final adagio. There is no trace of the »Divine Spark« (»Götterfunken«).

Literary musical poetry takes on new dimensions

But there is more to Leverkühn than nihilism. Like Beethoven or Schoenberg, he has an intrinsic desire to expand the boundaries and possibilities of art. Thomas Mann also explores the limits of music in »Doktor Faustus«, at least in terms of its literary possibilities. He describes Leverkühn’s fictional compositions in such vivid language and with such a wealth of detail that they almost become audible when reading. In Mann’s work, literary musical poetry reaches a new dimension. It stands to reason that Wagner and his concept of the ›Gesamtkunstwerk‹ inspired Mann to venture into a new form of intertwining literature and music. In »Doktor Faustus« this takes its most extreme form: music becomes the narrative as well as aesthetic core of the novel.

Music as a key to the inner lives of the characters

Even before his exile, music played an important role in Thomas Mann’s works. In 1907, he wrote to the composer Carl Ehrenberg that he was already doing »as much music as one can reasonably do without music«, thereby rejecting Ehrenberg’s request to write an opera libretto for him. Music appears as an important narrative component in his early novellas, such as »Der kleine Herr Friedemann« (1897) and »Tonio Kröger« (1903), as well as in his major novels »Buddenbrooks« (1901) and »Der Zauberberg« (1924). It takes on the role of fatal foreshadowing or helps bring about spiritual liberation. It is a key to the inner lives of the characters and often a first hint of coming tragedies – those who consciously perceive the music in Mann’s works are always one step ahead of the narrative.

A leading figure to this day

As it is the 150th birthday of the writer this year, Thomas Mann is showered with considerable media attention. In many respects, attempts are being made to shed a new light on Mann – especially regarding his political views – and to make his work accessible to a wider audience. The publishing house S. Fischer Verlag is striving to open up new approaches to the great storyteller with its new paperback editions of his work in a modern design (and, not to be forgotten, with a special Playmobil figure). Perhaps it is also helpful to ask about Thomas Mann’s ›ultra-ness‹. Less ultra-bourgeois, certainly ultra-political but above all ultra-obsessed with music. Serenus Zeitblom, the narrator in »Doktor Faustus«, explains it clearly in the novel: Music stands for everything. There is hardly a writer to whom this is more applicable to than Thomas Mann.

- , Kreuzkirche

Thomas Mann Fellows

DiscourseAida Baghernejad, Prof. Dr. Friedhelm Marx, Dr. Nils C. Kumkar